A modest green has returned to the Sepulveda Basin’s South Reserve – but many of its former wildlife residents have not.

It’s been nearly 2 ½ years since the Army Corps of Engineers unceremoniously ripped apart and plowed over 48 acres of the wilderness area that’s nestled in the traffic-laden corner between the 405 and 101 freeways. After the initial media uproar that involved politicians, environmental groups and local citizens, the dust seems to have settled on the landscape that once welcomed numerous birds including the California thrasher and the endangered least Bell’s vireo. But no more.

At a recent bird walk through both North and South Reserves, Kris Ohlenkamp from the San Fernando Valley Audubon Society says he recorded 63 species of birds, but only 5 were spotted in the South Reserve.

“I am surprised by the lack of diversity in the area,” he says as he walks through the area, pointing out where trees and shrubs were bulldozed over on that fateful December day. Late last year, the Army Corps removed most of the non-native trees on the reserve which now opens up the land for natives to recapture the land. (That removal was welcomed; groups like the Sierra Club, SFVAudubon, California Native Plant Society and others were also informed about the removal so there were thankfully no surprises.)

Today, young cottonwoods and box elders are regaining the ground and much of the overturned land is now covered with plant life, including native species. Butterflies and bees scour the offerings, but bird songs that are noisily heard non-stop in the North Reserve are strangely intermittent here.

Ohlenkamp stops near Haskell Creek where the only remaining non-native trees (trammel ash) stand; removing these thickly packed trees would have been too problematic and disruptive, he says. “Listen,” he instructs as he turns his head upward. “Nothing. No birds here. I don’t understand why.”

Indeed, many feathered residents that once took up nest in the South Reserve have been spotted now in the North, including about six pairs of California thrashers and three pairs of least Bell’s vireos.

Sure, here hummers zip through the sky, yellow warblers carry a solitary tune to a nearby tree, song sparrows dart among the branches. Down at the confluence of the creek to the L.A. River, you can spy all kinds of shorebirds. But there is a decided….emptiness…to the South Reserve that you can’t quite put your finger on.

Maybe it’s because this is a place without a specific plan or clear direction for its future. Since the Army Corps changed leadership after the December Bulldozing Debacle with the announcement of Kimberly Colton as Colonel, SFV Audubon and other groups have been engaged on and off with officials on the direction for the South Reserve. (Currently L.A. Parks and Recreation manages the North Reserve.)

There have been many discussions about the original 1981 Master Plan for the South Reserve that includes a proposed pond, lake and winter seasonal marsh. The pond was previously dug, but never filled with water.

Ohlenkamp stops at an open space flanked to the west of Haskell Creek before it converges with the L.A. River. “This would be a perfect place for a seasonal marsh,” he says adding that no trees would have to be removed; only a water source would have to be diverted to keep the area moist especially in the winter months. A marsh would encourage a variety of wildlife – and provide a natural barrier to homeless encampments and hidden enclaves used for lascivious rendezvous. “It would be a good deterrent,” says Ohlenkamp. “Soon these trees will grow tall and we’ll have the same problem all over again.”

What Ohlenkamp and company are specifically waiting on is a Vegetation Management Project which would outline how the Army Corps plans to care for and maintain these acres.

“It’s been a year of waiting,” he says. “Things are moving…but at a glacier-pace.”

Despite that, Ohlenkamp is happy that groups are being invited to the Army Corps table to discuss the future of the South Reserve. “They have kept us involved and listened to us, their attitude has changed, but we get the feeling we are not a priority for them,” he says.

That might be the rub. After all, the Corps is involved in a myriad of other high-profile projects including a storm damage reduction project in Encinitas-Solana Beach and the very popular Los Angeles River Ecosystem Restoration Feasibility Study.

The official word from the Army Corps on Sepulveda Basin’s Vegetative Management Project is that it is “nearing completion” as is the Environmental Assessment.

From a Corps email to SoCalWild:

“Following a meeting with stakeholder representatives in December 2014, the Corps’ contractor, RECON Environmental, has updated the proposed array of alternatives to include the feedback from the stakeholders. The update is being reviewed now by the Corps team before readying it for public review.”

“Regarding the Sepulveda Basin Master Plan, which was updated in 2011; we plan to issue errata sheets, to include information received by the stakeholder groups, but the schedule for doing so has not yet been established.”

As it goes, five versions of a Master Plan have been discussed all which, according to Ohlenkamp, would be acceptable to community and environmental parties. “Again, we are waiting for movement.”

Maybe that’s what’s missing from the walk in the South Reserve. A sense of movement. A flurry of wildlife activity, a bustling of busy-ness that comes from nature fully alive.

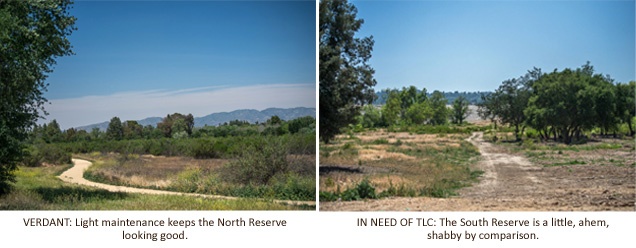

There’s no question that the South Reserve has adjusted from its earlier trauma but it’s certainly not flourishing like the nearby North Reserve. These are, in essence, fallow acres waiting for the bureaucratic stars to align. Just like certain seeds that can wait for years for the right mixture of water, sun and time to finally sprout, so goes the South Reserve.

So for the time being, nature waits alongside those humans who are connected to Sepulveda Basin, all anticipating a day when birds will once again fill the wild landscape with nests and songs.

— Brenda Rees, editor. Photos by Martha Benedict (c)