On the banks of the San Gabriel River, up from Seal Beach, a variety of people scan the slate gray waters for wildlife. On different sides of the river, citizen scientists, families with kids, retired folks and young adults study the slate dark gray waters, not for birds, but for one of nature’s most tantalizing swimmers, the Pacific green sea turtle.

Sure, the thought of sea turtles brings to mind tropical waves and white sandy beaches for egg-laying, but – as strange as it may sound – Pacific greenies are part of the SoCal marine landscape, and these swimmers are making do with the habitat options before them.

They are found in pockets in Anaheim Bay and further south in Los Alamitos Bay in San Diego; the bale of turtles swimming in the San Gabriel are as north as the greenies go given the water temperature – which in the river is about 80 degrees thanks to runoff from the nearby shoreline power plant.

All juvenile youngsters, these green dudes chill out in a predator-free river life, enjoying jellyfish, fish, bugs and vegetation; when they are adult, they’ll be strict plant-eaters, preferring sea grasses which are few off SoCal coastlines these days.

“There has been some indication that the turtles historically have been in the river even before the power plant was built,” says Cassandra Davis, Education Volunteer Coordinator for the Aquarium who oversees a citizen science program of turtle trackers. “The warm waters may not be the only reason they are here. We just don’t know.”

But Davis and her turtle team do know how to count, observe and record turtle behavior. Turtle lovers have been gathering data and photographing the greenies since 2008, and in 2013, the aquarium along with NOAA initiated the program to monitor turtle behavior in the river.

Once a month, volunteers spread out in groups over a two mile-stretch of the river to observe and count surfacing turtle heads. (An underwater camera experiment proved futile against the murky waters). Rule of thumb for turtle counters: every 50 surfacing heads usually means four individual turtles.

Overall, it’s difficult to estimate how many turtles are in the river; Davis says it’s definitely “between 4 and 400. We are very conservative with numbers,” she explains with a laugh. When pressed, she admits the number is probably more than 10 and less than 30 – but this is just an educated guess, she warns.

Numbers aside, public turtle spotting is possible daily on the river – viewing locations are best accessed through the existing bike path near Studebaker near the power plant; the bridge over Westminster Avenue is also an excellent location for walkers.

A more formalized viewing experience is the free monthly Turtle Trek sponsored by the Los Cerritos Wetlands Land Trust where naturalists from Tidal Influence lead trekkers around the wetlands (including working oil derricks), native plant nursery and finally to see the turtles.

Naturalists explain that one day it’s hoped, when the power plan goes offline, these cold-blooded swimmers will inhabit the nearby Los Cerritos Wetlands which is slowly being transformed back to its original state – a variety of nonprofit and government agencies have been involved in restoring the land for eight years now, cultivating, replanting and allowing nature to take back the land.

At some point in their lives (sea turtles can live 80 years in the wild), the juvenile greenies will head out into the ocean to test themselves against bigger turtles, seek out mates and forage salt-water vegetation. Life for a sea turtle can be precarious off SoCal coastlines – pollution, loss of sea grass and ingesting plastic can disrupt and eventually kill them. Getting entangled in fishing line is another big problem.

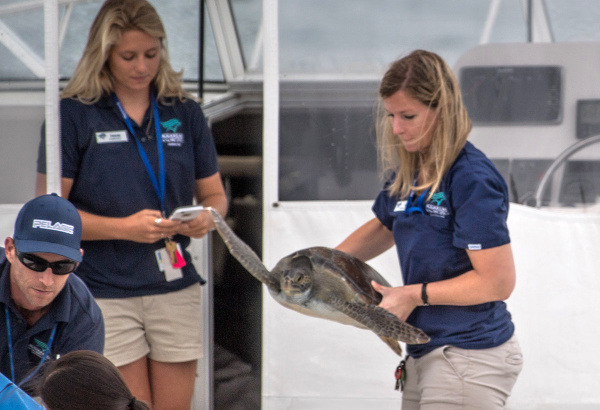

Wrapped in filament and struggling, two juvenile Pacific greenies were recently taken to the Aquarium of the Pacific for medical attention and rehabilitation. One was found with a hook in its throat; the other was accidentally caught by a fisherman who contacted authorities for help. (See a turtle in trouble? Call NOAA’s hotline at 866-767-6114.)

After five weeks of rehabbing in a fancy aquarium tank, the second sea turtle was deemed fit to return to its ocean home. Placed in a cart and wheeled into a boat, the turtle and caretakers traveled about a mile off the Long Beach shore before the swimming reptile was released — with a plop — as onlookers cheered and applauded.

As the boat turned to motor back to the harbor, the sea turtle popped its head out of the ocean waters for a brief moment. Maybe it was thanking the staff for the medical attention and its aquarium vacation or maybe it was getting its bearings to swim back to its buddies and the safety of the San Gabriel River.

— By Brenda Rees, Editor

— Photographs courtesy of Martha Benedict, Kadi Erickson and Irene Kurata