For three years, Southern California rescue and treatment centers for marine mammals were overwhelmed with young stranded California sea lions. Day after day, emaciated and weak pups arrived with saggy skin and sad eyes.

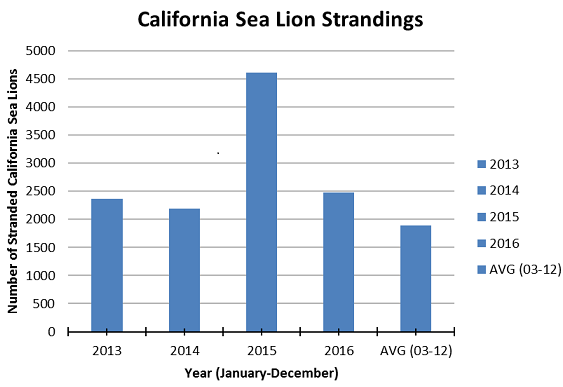

Staff at the five SoCal rescue facilities went into emergency mode, working round the clock to treat malnourished youngsters, many after being born on the Channel Islands were being abandoned by their mothers that couldn’t find enough fish. It’s estimated that between 2013-2016, there was a 2 to 4 times increase in the number of strandings, with 2015 being the hardest hit year.

Today, SoCal is still under the Unusual Mortality Event (UME), the official NOAA desination, but officials and rescue facilities are seeing reduced numbers of sea lion pup strandings this year – and anticipate a return to normal levels.

Even so, that doesn’t mean easy and quiet days at rescue facilities which are currently bracing for a spring ocean algae bloom that can produce domoic acid poisoning in California sea lions. Already high numbers of sea lions are being admitted to rescue facilities showing toxicity symptoms such as lethargy and unawareness.

Pregnant and nursing moms could once again endanger the health of their young pups that depend on their mothers for food the first year of their lives.

Spring typically brings natural algae blooms. But those blooms are intensified by water runoff that contains land-based fertilizers. Surface fish like sardines and anchovies eat the algae which, in high concentrations, can produce neurotoxins that can destroy the brain. Sea lions feasting on surface fish run the risk of ingesting the toxic or passing it along to their pups.

Marine mammals are “our canaries in the coal mine when it comes to assessing the health of the ocean,” says Justin Viezbicke, West Coast Stranding Coordinator with NOAA. “Ocean conditions are constantly changing, and our job is to monitor those changes. Marine life can indicate for us what’s happening in the water before we get out there.”

David Bard, Development Manager and Animal Care Quality, at the Marine Mammal Care Center in San Pedro says his facility has just admitted 15 suspect cases of domoic acid poisoning which will keep his staff and volunteers very busy. There is no cure for domoic acid poisoning; sea lions are given supportive fluid therapy and anticonvulsants and monitored to see if, despite brain damage, they can be successful hunters and be released back into the ocean.

Adding to the domoic toxicity cases, Bard is also worried about “an unusual number of elephant seal pups we have received. They tend to strand in February through April, but we are seeing more than average numbers right now.” More than 50 ellies are currently at the facility.

Indeed, walking through the pens at the care facility, ellies are everywhere, barking loudly at each other, slapping their long bodies forward on the outdoor flooring and peering up at guests and visitors with those large velvet eyes. Visitors are welcomed to visit with the patients daily that are cared for in the 15 enclosures at the seaside facility.

These elephant seal youngsters are on their way to being released; they typically stay for three months, cared for by staff and an enlarged group of volunteers who’ve responded to the UME and the overwhelming sea lion pup strandings.

“There have been a few silver linings to the UME and our seasonal/auxiliary volunteers are one of them,” explains Bard. The hard-working vols perform animal support services (laundry, dishes, etc.) which allow staff and medical team to focus directly on the patients. “They have proven invaluable,” he says.

The UME also paved the way for the center to receive local grants and awards that provided community interns and HAZWOPER training – skills that proved beneficial during the Refugio Oil Spill of 2015.

And finally, the UME helped raise public awareness about the work of the center and the ecology of marine mammals, according to Bard.

Southern California is still technically experiencing UME – officially will make a formal assessment and declaration near the end of the year – but marine biologists, rescue officials and the pinniped-loving public are hoping for good news. “There was a fear that the UME would be the new normal,” says Bard. “We really don’t want to go through that again.”

NOTE: Click here to learn more what to do if you see marine mammal that appears to need help.

Story: Brenda Rees, Photos: Martha Benedict and Brenda Rees