Pictures are worth a 1,000 words – and for the creators and users of iNaturalist, that saying speaks volumes. Volumes of data, that is.

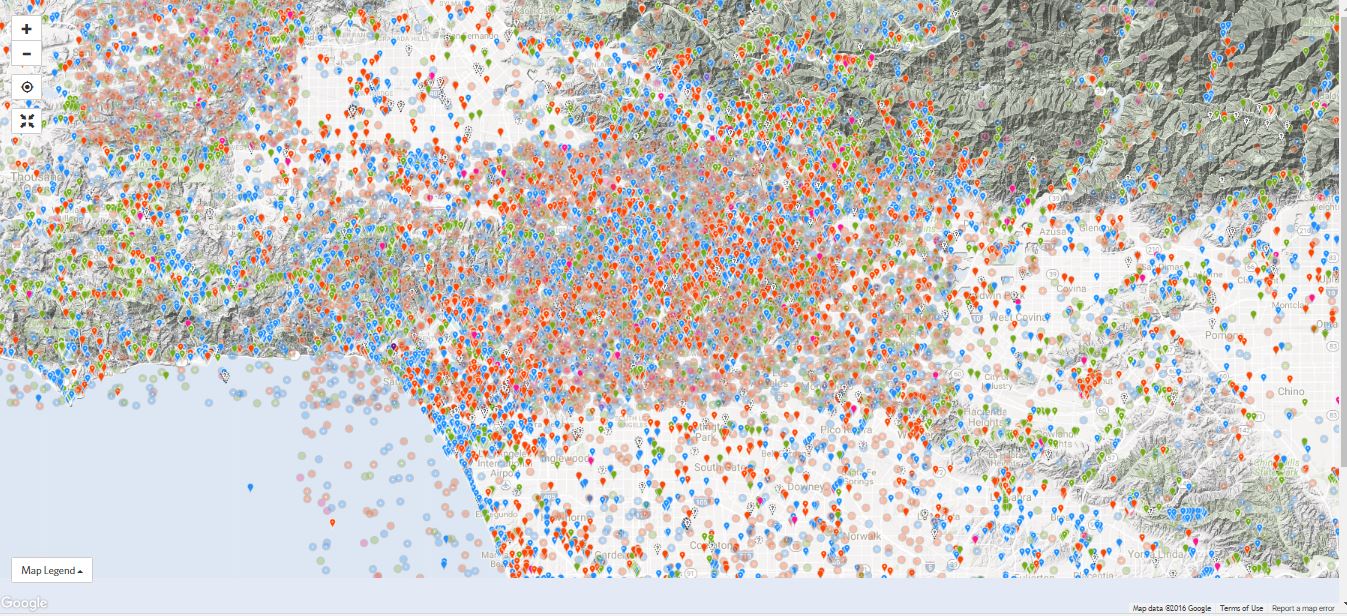

With more than 3 million observations from more than 250,000 users logged into the online platform since its initial launch in 2008, iNaturalist has become the go-to source for scientists, biologists, teachers, students, stay-at-home parents, hikers, and anyone who wants to better understand the natural world around them.

For scientists, iNaturalist provides revolutionary field data they could not get on their own; for others, iNaturalist offers identification of the strange bug that’s been crawling up the backyard drain pipe.

For other users like B.J. Stacey of San Diego, the electronic crowdsourcing website gives him an outlet for the thousands of images he has snapped as an amateur outdoor photographer.

“I’ve been photographing nature since I was a kid,” he says explaining that birding propelled him outdoors but that he was also fascinated with other critters “like snails, lizards and butterflies. iNaturalist put value on what I’ve photographed over the years.”

Stacey has the dubious honors of being Number One Observer on iNaturalist with nearly 45,000 images to his name that includes 700 species of birds, 1,200 insects, 1,200 plants and more. “I always have my camera with me and I just go out to see what I can find; I just love to learn.”

iNaturalist began as a master’s project by three grad students in the Bay Area who created a place where scientists and students could share images of natural flora and fauna in the name of research. With the dawn of citizen science, the general public wanted to be part of the action and eagerly jumped into the mix.

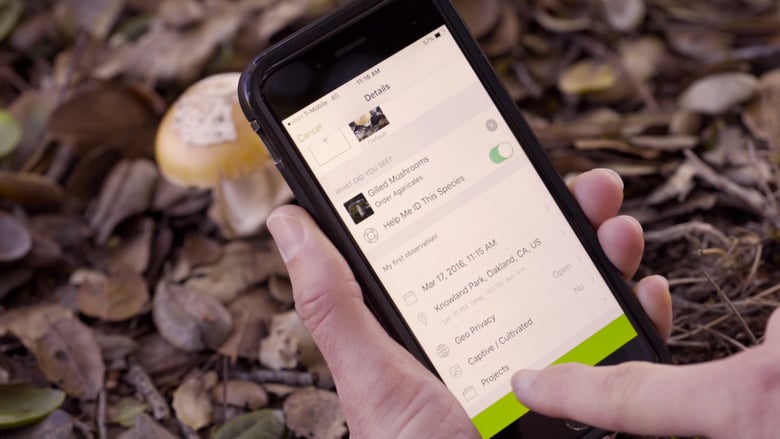

If you haven’t been on iNaturalist, the platform is an easy-to-navigate, social media site. Users create an account to begin uploading images that are tagged with location and date. Community experts examine the photos and correct or confirm a species designation; when three experts agree, the image is deemed “museum grade” and it is uploaded to the Global Bioinformatic Data Facility (GBIF) which is used by scientists all over the world.

Anyone can create a specific project on the site and cull images or have participants upload photos directly to that project; in SoCal, there are specific species projects (flying squirrels, fungi, stinkbugs, mule deer, etc.) as well as event or location-centric (LA River, Wildlife of the Santa Monica Mountains, etc.).

iNaturalist was acquired by the California Science Academy in 2014 and gets about 5,000 uploaded observations per day – with new technology being explored and incorporated.

“The community has gotten so much bigger than when it was conceived,” says Scott Loarie, who helps oversee the site. “Our main challenge today is to deal with the hits and scale any new developments to accommodate the growing amount of traffic.”

Even with the convenience of the iNaturalist app, most observations are uploaded via the website; Loarie thinks it’s because hard-core photographers rely on the quality of a SLR camera lens not a smart phone for details.

But iNaturalist is not only photos; users can upload sound (limited capacity, tho) which can help identifying frogs, birds and other vocal critters. Loarie says there have been many requests to add video into the platform. Right now, users who want to share moving images must link a YouTube video to iNaturalist – not very user-friendly.

With the success of Pokémon Go this year, iNaturalist folks have been kicking around ideas to engage app users so the system is less passive and more interactive and game-like. One idea syncs user locations to the app and can ping the user with a search request such as: “We see you are near this area; would you mind seeing if you can find this particular critter or plant?”

This natural world scavenger hunt could “fill the gaps of data,” says Loarie while “mobilizing people to look for specific species.”

Integrating Image Recognition software into the program is also being discussed, says Loarie, who has been following the improvements that technology has taken in the recent months. iNaturalist has met with engineers at Caltech’s Vision Laboratory and the Visipedia (Visual Encyclopedia) Program about possible collaborations. “I am sure that Image Recognition will play a role in the future,” he says but adds that experts in the field will also be essential to iNaturalist.

“The technology can get better and can help teach the community which leads to a more educated, more informed community,” Loarie says adding that iNaturalist has the ability to be a conservation tool to produce data over time about the abundance or decline of a species in a certain distribution area.

“The success of iNaturalist depends on the people using it,” points out Loarie adding that “local champions” like school teachers or professors have enormous impact on how the site is being used.

One of those champions is Greg Pauly, director of Herpetology at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles who has turned to data from iNaturalist for local and national projects.

Pauly launched the RASCals project at the NHM three years ago and it has garnered more than 16,000 images of SoCal herps from more than 2,000 participants. Similarly, GeckoWatch expands the reptile hunt to track the national distribution of non-native geckos.

Through Pauly’s projects, important discoveries have been made about nonnative and new species being found which has led to citizens being part of peer-reviewed publications.

Checking out the reptile and amphibian daily observations (“I’m selfish, I always want more data”), Pauly would love to see the platform implemented regularly in schools and neighborhood groups. He’s adamant that this kind of crowdsourcing is the wave of the future when it comes to collecting natural data. “It’s easier to get data from an isolated rain forest than in Los Angeles because of all the private property we have here,” he says. “There is no other way to do this but with private citizens.”

Overall, the data collected on iNaturalist will, as Pauly says, “outlive us all and help us understand the world especially how species are dealing with climate change, habitat loss and other factors. This knowledge can help us strategically move forward as a society especially for urban planners in areas like Los Angeles.”