Wiggling, fidgeting and anxious. The sixth grade class at Sun Valley Magnet Middle School were painfully waiting their turn to step to the front of the class. They tried to contain their nervous energy and nearly lost the battle. Busting at the seams? An understatement.

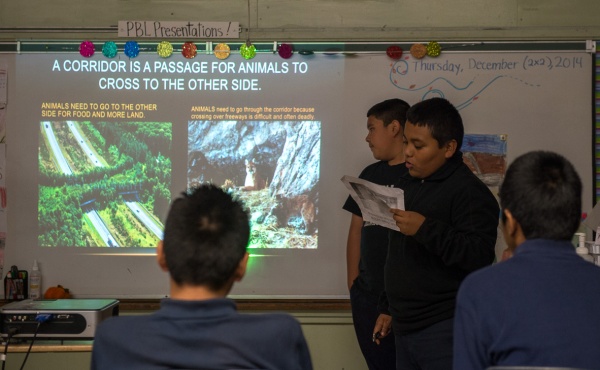

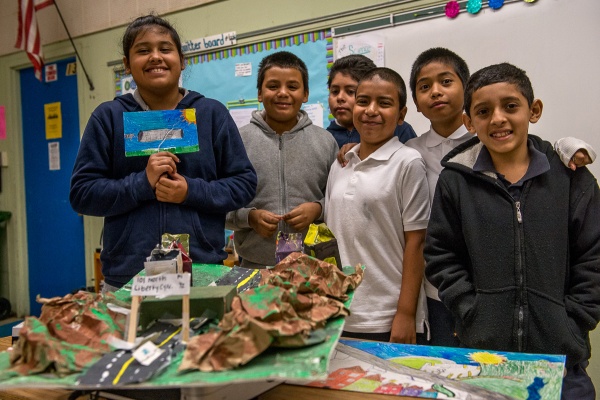

One by one, groups of three and four came forward in front of fellow classmates and students from neighboring classes. The Science Dudes, The Animal Finders, the Bobcats and more. Each group had a presentation that, while similar in topic, reflected different facts, personal narratives, and elaborate Powerpoint flourishes.

“Urban sprawl affects our indigenous animals,” presented one student while an image of a bobcat on a tree flashed on the board.

Later, another group came up, and showed a photo of three young cougars. “Three baby mountain lions were killed on the 126 freeway,” described the student. “The solution is we need to stop the road kill.”

“Wildlife corridors are needed for animals to move from one habitat to another,” declared another student about the proposed passageway over Liberty Canyon on the 101 freeway. “The importance of biodiversity is to keep our ecosystems stable.”

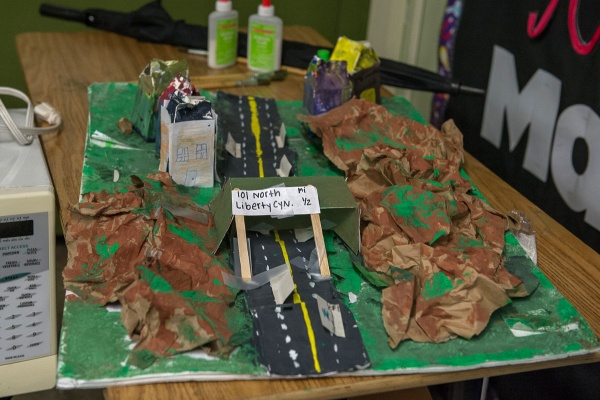

Most presentations were electronic but one group, the Thunder, created a handmade model of what a proposed wildlife corridor would look like. Plenty of cardboard, construction paper, milk cartons and glue were put into the model that depicted a green bridge spanning a concrete freeway with buildings off to the side.

“Animals need to move around to expand their territory and find a mate,” stated one Thunder member. “These bridges need to look natural and blend into their surroundings so animals will use them. They need California native plants like coyote bush and California lilac.”

Using a real-world example of the current wildlife corridor fits in well with the Project Based Learning (PBL) that’s the norm at this Environmental Studies Through Arts Academy magnet school.

The Wildlife Corridor lesson was more than two months in the making and involved vocabulary words, research on the internet, interviews, a trip to the Natural History Museum and, perhaps the most inspiring aspect, a tour of Liberty Canyon with Anne Dittmer, CSUN professor who is intensely interested in the proposed corridor.

Students learned first-hand about the problem and solutions, said teacher Joceyln Medina who first heard about the plight of habitat-boxed mountain lions and bobcats two years ago when Professor Dittmer was her instructor. “The issue was just perfect for the type of learning we advocate here in the classroom,” she said. “Active, real world and participatory.”

“We actually walked the same route that the mountain lions would have to take to get from the north side of the freeway to the south side, and I think that got their attention,” said Dittman. “It was just an ordeal for them to get across without getting squished. Cars, and noise, and all suddenly got more real. I had hoped that the walk would impart just how scary the whole experience could be for larger predators…and how much we needed a real corridor in the area.”

In addition to touring Liberty Canyon, Professor Dittmer brought the youngsters to explore nearby Malibu Creek to understand the landscape – which is home to many critters that could potentially use the corridor.

After the presentations, students – now a bit more relaxed – were eager to share their knowledge and discuss their experiences related to the project. Many still had the image of Liberty Canyon in their heads. “There were just mountains there.” “How long will it take to build the corridor?” “I wish they could just dig a hole for the animals to move around.” “I saw lots of little holes in the ground. I think it was the under-squirrels.” “What does the P stand for in P-22?”

Students knew the sad story of seeing dead animals on the street – raccoons, squirrels, even birds. Many advocated in their presentations that adults (including parents) should drive cautiously when they know that wildlife is around. Still, even with careful human eyes, that doesn’t mean a critter won’t take a chance at crossing.

The students were shocked to learn that often young mountain lion cubs in the Santa Monica Mountains have been killed by their father in the juggle for territorial dominance. “That’s just wrong.” “Why?” “Sick.”

Yes, the ways of nature can be hard to grasp, but this fact sealed for the student’s the pressing need to establish the corridor.

“We just need to share what we have with the animals,” said one very wise sixth grader. “We should just do it. Now.”

— Story by Brenda Rees, photos by Martha Benedict