There’s a long road ahead for SoCal sea star populations that are slowly recovering from the Sea Star Wasting Syndrome that hit the area in late 2013 – and SoCal residents are encouraged to help play a part in monitoring the process.

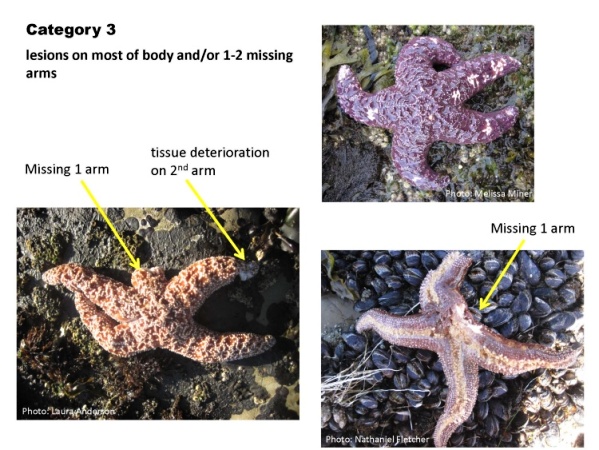

Four years ago, SoCal coastlines and intertidal outcroppings were strangely devoid of sea stars, victims of the debilitating event which many experts hypothesize as a virus or bacteria. (Contrary to social media hype, scientists say that the syndrome was not the result of the Fukushima meltdown.) Developing lesions, millions of infected sea stars lost limbs and had their bodies turned into goo. Similar wasting events have been recorded in the past, but none of this magnitude; in which diseased sea stars were observed concurrently from British Columbia, Canada to Baja California, Mexico.

Now, marine biologists are observing populations of ochre sea stars SoCal waters; some sea stars appear healthy but some, sadly, still show signs of the disease.

Marine ecologist Stephen Whitaker has been monitoring 20 sites around the Channel Islands National Park as part of a long term monitoring project and submitting observations to MARINe, a multiagency consortium that has been collecting and sharing data on intertidal species from Alaska to San Diego. Whitaker recently visited 16 sites and reports that four sites have between 13-28 sea stars, while others have less than five or none at all. This is a dramatic decrease compared to before the disease in 2013 when abundances averaged several hundred individuals at most sites.

At some sites, early signs of sick sea stars have been observed, says Whitaker. “But we are not the only one in the MARINe group to see these early symptoms,” he says about the syndrome that stubbornly still persists, albeit at low levels. “This has been the same with other groups up and down the coast.”

There are rays of hope. While Whitaker monitors specific island sites, he has observed sea stars in other areas of the park. “I’ve seen dozens of ochre sea stars at other locations,” he says. “They are there.”

It will take several years – maybe decades – for sea stars to grow and reach a healthy abundance; at one time recorded sea stars numbered in the hundreds and above 1,000 at sites within the national park.

Some species were hit harder than others, explains Whitaker. Stars in colder deep waters often escaped diseases that wiped out their fellow stars in shallower waters. But this recent event even reached those deep dwelling stars. “That’s one reason that temperatures may not play a factor in this wasting event,” he explains.

Collecting data and sharing with experts is crucial to understanding the cycles and factors involved in such large-scale die-offs, says Whitaker. “The consortium does a good job of organizing samples from more than 100 sites from San Diego to Alaska,” he explains, “but we really appreciate and depend on citizen scientists’ observations.”

Indeed, locations between MARINe monitoring sites are where citizen scientists can play an important role, says Melissa Miner of MARINe. “What people are seeing, especially if they frequent a certain location, could be really valuable to us in understanding SSWD,” she says. “Not just diseased stars either. We want to know what species are healthy as well as sick.”

Interested folks can check out identification and symptom guides to specific sea star species — including juvenile ones — and learn how to submit observations at MARINe’s website. You’ll be asked to record specific site information, sea star species seen/not seen and other important information like the location type (sandy beach, intertidal, etc.) and depth; sending photographic images is a big plus.

“Southern California was hit very hard,” says Miner who is helping to coordinate monitoring efforts along U.S. coastlines. “Before the event occurred, Southern California populations were building up. Now it will likely take decades to return to those levels.”

Indeed, Miner says that researchers are discovering that north of Point Conception, large numbers of juvenile stars have been observed at some sites, a good sign that some sea star species are spawning and “recruiting” new individuals. But south of the Point…not so much. Still, the typical spawning season is in spring and fingers are crossed for babies.

Researchers are also witnessing new sea star behaviors, especially involving how fast sea stars are maturing, says Miner. A quarter-sized star used to mean a 2-year-old. Now, that same size may mean a 1-year old individual. Miner says multiple factors are probably at play, like food availability, habitat, etc. But one theory suggests these stars are spawning and maturing as a “stressed-out last ditch effort to reproduce” in light of such low numbers.

Researchers are also learning more about basic sea star biology from the event, says Miner. “By tracking pulses of recruits over time, we can learn more about growth rates, and how they might vary among sites,” she says. Researchers are also learning how a decline in sea stars can lead to changes in the ecosystem; with no sea stars predators, urchin populations are mushrooming in some regions, which affects numerous other species.

“The marine ecosystem is tremendously complex and we understand so little of it,” sums up Whitaker.

— Brenda Rees, Editor